Today's post is from guest author Heather Johnston.

The text is an excerpt from the 1987 novel Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami in which the narrator reflects on his experience after the death of his close friend Kizuki.

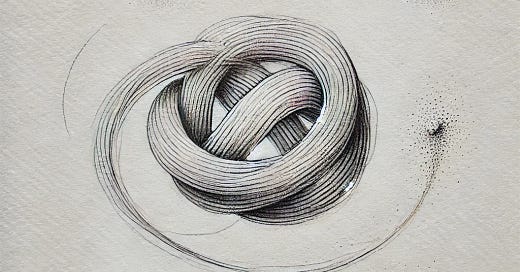

I tried hard to forget, but there remained inside me a vague knot-of-air kind of thing. And as time went by, the knot began to take on a clear and simple form, a form that I am able to put into words, like this:

Death exists, not as the opposite but as a part of life.

Translated into words, it's a cliché, but at the time I felt it not as words but as that knot of air inside me. Death exists — in a paperweight, in four red and white balls on a billiard table — and we go on living and breathing it into our lungs like fine dust.

Until that time, I had understood death as something entirely separate from and independent of life. The hand of death is bound to take us, I had felt, but until the day it reaches out for us, it leaves us alone. This had seemed to me the simple, logical truth. Life is here, death is over there. I am here, not over there.

The night Kizuki died, however, I lost the ability to see death (and life) in such simple terms. Death was not the opposite of life. It was already here, within my being, it had always been here, and no struggle would permit me to forget that. When it took the seventeen-year-old Kizuki that night in May, death took me as well.

I lived through the following spring, at eighteen, with that knot of air in my chest, but I struggled all the while against becoming serious. Becoming serious was not the same thing as approaching truth, I sensed, however vaguely. But death was a fact, a serious fact, no matter how you looked at it. Stuck inside this suffocating contradiction, I went on endlessly spinning in circles. Those were strange days, now that I look back at them. In the midst of life, everything revolved around death.

In the inaugural Secular Mornings post, Tyler quoted Joe Carlsmith's observation that some forms of secularism lose "existential intensity". Personally, I am usually happy to repress existential intensity. I consider it a blessing that my mind so often redirects my attention away from the vast and incomprehensible and toward the mundane. I feel fortunate that I can usually suspend my disbelief about matters of life and death, and treat deadlines at work and remembering my friends' birthdays as the most pressing matters I have to attend to.

Despite this, there are moments when it is valuable, or unavoidable, or both, to contemplate the more difficult aspect of existence. Murakami's narrator describes the poignant and unforgettable awareness of mortality that can come when we lose someone dear to us. This kind of perspective change, even if it doesn't last long, gives a different quality to our experience of the world. It's not the kind of perspective change that happens when we learn a new material fact about the world or change an opinion; it's a foundational change in how we relate to the entirety of existence.

Murakami's passage reminds me of what Sasha Chapin calls befriending the void:

Chapin doesn't describe the void as being awareness of mortality in particular, but more generally as a sense of nonexistence. He recommends embracing this awareness as a deliberate practice. He also tells us that, while it may be frightening to approach, this sense of nonexistence is not necessarily negative. He writes, "The void is a generous thing. It continuously spawns every moment of your life, the spectacular and painful display we all get to enjoy. It doesn’t want to destroy you. It seems to want to create you."

There is an opportunity that arises from holding the awareness of our own mortality close. And I believe that Sasha Chapin is wise to notice that the nearness of nonexistence is not only scary, but also generous.