Good morning.

Today’s text comes from a 2017 essay by John Salvatier.

My dad emigrated from Colombia to North America when he was 18 looking looking for a better life. For my brother and I that meant a lot of standing outside in the cold. My dad’s preferred method of improving his lot was improving lots, and my brother and I were “voluntarily” recruited to help working on the buildings we owned.

That’s how I came to spend a substantial part of my teenage years replacing fences, digging trenches, and building flooring and sheds. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned from all this building, it’s that reality has a surprising amount of detail.

This turns out to explain why its so easy for people to end up intellectually stuck. Even when they’re literally the best in the world in their field.

Consider building some basement stairs for a moment. Stairs seem pretty simple at first, and at a high level they are simple, just two long, wide parallel boards (2” x 12” x 16’), some boards for the stairs and an angle bracket on each side to hold up each stair. But as you actually start building you’ll find there’s a surprising amount of nuance.

The first thing you’ll notice is that there are actually quite a few subtasks. Even at a high level, you have to cut both ends of the 2x12s at the correct angles; then screw in some u-brackets to the main floor to hold the stairs in place; then screw in the 2x12s into the u-brackets; then attach the angle brackets for the stairs; then screw in the stairs.

Those goddamn stairs.

Next you’ll notice that each of those steps above decomposes into several steps, some of which have some tricky details to them due to the properties of the materials and task and the limitations of yourself and your tools.

The first problem you’ll encounter is that cutting your 2x12s to the right angle is a bit complicated because there’s no obvious way to trace the correct angles. You can either get creative (there is a way to trace it), or you can bust out your trig book and figure out how to calculate the angle and position of the cuts.

You’ll probably also want to look up what are reasonable angles for stairs. What looks reasonable when you’re cutting and what feels safe can be different. Also, you’re probably going to want to attach a guide for your circular saw when cutting the angle on the 2x12s because the cut has to be pretty straight.

When you’re ready to you will quickly find that getting the stair boards at all the same angle is non-trivial. You’re going to need something that can give you an angle to the main board very consistently. Once you have that, and you’ve drawn your lines, you may be dismayed to discover that your straight looking board is not that straight. Lumber warps after it’s made because it was cut when it was new and wet and now it’s dryer, so no lumber is perfectly straight.

Once you’ve gone back to the lumber store and gotten some straighter 2x12s and redrawn your lines, you can start screwing in your brackets. Now you’ll learn that despite starting aligned with the lines you drew, after screwing them in, your angle brackets are no longer quite straight because the screws didn’t go in quite straight and now they tightly secure the bracket at the wrong angle. You can fix that by drilling guide holes first. Also you’ll have to move them an inch or so because it’s more or less impossible to get a screw to go in differently than it did the first time in the same hole.

Now you’re finally ready to screw in the stair boards. If your screws are longer than 2”, you’ll need different ones, otherwise they will poke out the top of the board and stab you in the foot.

At every step and every level there’s an abundance of detail with material consequences.

It’s tempting to think ‘So what?’ and dismiss these details as incidental or specific to stair carpentry. And they are specific to stair carpentry; that’s what makes them details. But the existence of a surprising number of meaningful details is not specific to stairs. Surprising detail is a near universal property of getting up close and personal with reality.

…

Before you’ve noticed important details they are, of course, basically invisible. It’s hard to put your attention on them because you don’t even know what you’re looking for. But after you see them they quickly become so integrated into your intuitive models of the world that they become essentially transparent. Do you remember the insights that were crucial in learning to ride a bike or drive? How about the details and insights you have that led you to be good at the things you’re good at?

This means it’s really easy to get stuck. Stuck in your current way of seeing and thinking about things. Frames are made out of the details that seem important to you. The important details you haven’t noticed are invisible to you, and the details you have noticed seem completely obvious and you see right through them. This all makes makes it difficult to imagine how you could be missing something important.

That’s why if you ask an anti-climate change person (or a climate scientist) “what could convince you you were wrong?” you’ll likely get back an answer like “if it turned out all the data on my side was faked” or some other extremely strong requirement for evidence rather than “I would start doubting if I noticed numerous important mistakes in the details my side’s data and my colleagues didn’t want to talk about it”. The second case is much more likely than the first, but you’ll never see it if you’re not paying close attention.

If you’re trying to do impossible things, this effect should chill you to your bones. It means you could be intellectually stuck right at this very moment, with the evidence right in front of your face and you just can’t see it.

This problem is not easy to fix, but it’s not impossible either. I’ve mostly fixed it for myself. The direction for improvement is clear: seek detail you would not normally notice about the world. When you go for a walk, notice the unexpected detail in a flower or what the seams in the road imply about how the road was built. When you talk to someone who is smart but just seems so wrong, figure out what details seem important to them and why. In your work, notice how that meeting actually wouldn’t have accomplished much if Sarah hadn’t pointed out that one thing. As you learn, notice which details actually change how you think.

If you wish to not get stuck, seek to perceive what you have not yet perceived.

I’m writing this on my laptop keyboard.

It seems like a simple enough piece of technology — a collection of fifty or so buttons that correspond to individual letters — but that’s just because we haven’t gotten up close and personal yet.

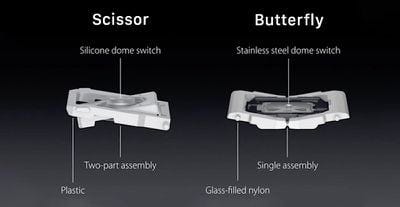

Have you ever had a keycap fall off? If you use an Apple device, you may have then seen the “scissor-switch” mechanism underneath each and every key — a pair of opposing plastic stabilizers joined by a hinge, allowing for an even keystroke with short travel as the “scissors” close.

That is unless your Macbook was manufactured between 2015 and 2020, in which case you have a “butterfly” keyboard where each key features a single, central metal hinge that compresses down in a “V” shape, like butterfly wings flapping.

What were the design advantages that led Apple to opt for the butterfly design in 2015? How did this trade-off against reliability (as now made infamous by a class action lawsuit against the company)? What eventually convinced Apple to reverse course?

I’ll leave these questions as an exercise for the curious reader.

When you notice something seemingly simple today — big or small, natural or manmade — try searching for the hidden details.